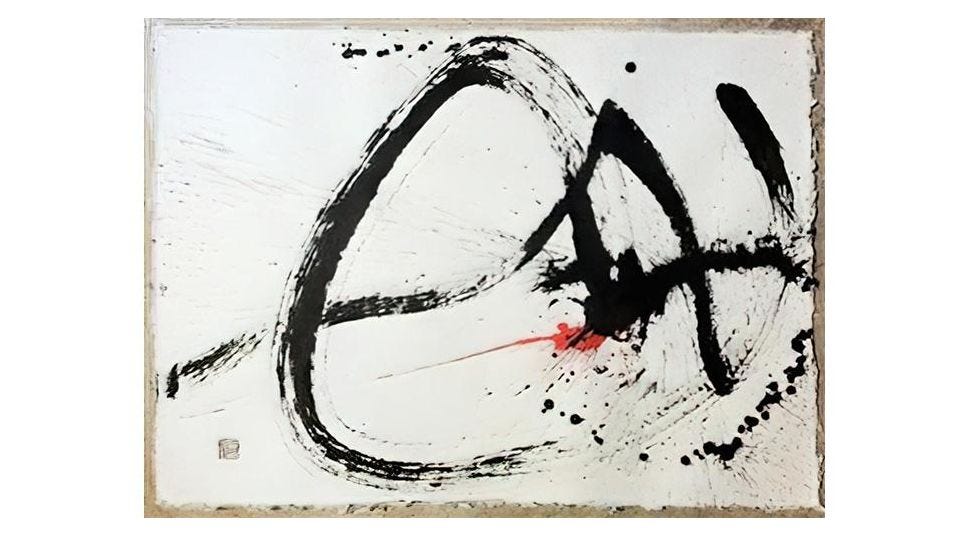

Featured Artist Interview: Peter DeWood

Peter DeWood is an artist and professional chef, inspired by his practice of Buddhism. He paints in the tradition of the Sumi-e brush artists, primarily on handmade mulberry paper from Thailand or cold press watercolor paper. A self-taught artist, he felt that he had to rebel against himself in a sense in order to paint in an authentic, free and self-expressed manner. He had to break through his own personal boundaries and blockages. In his own words: “When I started doing this art practice I was doing small pieces and it was very calculated and I was trying to emulate images I saw and copy styles and forms and as that grew over the years, the short few years I’ve been doing it, I’ve learned to trust myself and just let the artwork do itself.” What I found personally fascinating is how his spiritual practice grounds him and frees him at the same time so that the art can materialize.

Peter takes a disciplined approach to his work and guards his daily routine in his studio. Sometimes he works for 15 minutes and other times he works for hours on end, so although the time in the studio may vary, the daily commitment does not. Often he’ll have 5-6 pieces of paper lined up and paints both simultaneously and concurrently, capitalizing on the Zen aspect of the process. He has an interesting way of dealing with creative blocks. He doesn’t ignore the block but ‘sits’ with it, meditates and allows it to work through on its own.

In my interviews, I always like to know what the artist considers the biggest accomplishment in his or her career thus far. For Peter, it was being recognized by one of the Zen master painters, Max Gimblett of New Zealand, who Peter had reached out to for critique of his work and as a result, enjoys the friendship and support of the master.

Laura Jajko (LJ): I was just looking at your artist profile and I had no idea you were local. That is so cool. Are you a long time American Frame customer?

Peter DeWood (PD): No. For some reason I never knew about you guys and from what I gather, that is common in Toledo. A lot of people didn’t know about you guys.

LJ: We’ve failed in that regard. We’ve failed at getting the word out in our own community. I don’t know if you’ve been in the Showroom lately but we’re expanding and we’re going to put something special in there. We are hoping to make our mark locally by having a really great place where people can come.

PD: Yeah that’s awesome. I had a couple pieces framed there recently and I had the chance to come into the showroom and I feel lucky that you guys are so close and that I know about you now. It’s a good thing. You guys do a really great job.

LJ: Thank you. Are you a teacher?

PD: I’m actually a chef.

LJ: A chef? Wow! Where do you cook?

PD: At a country club.

LJ: What’s your specialty?

PD: I’m a big fan of Mediterranean cuisine and Indian food. I really enjoy anything I can put my heart into. I like to be creative but also stick to the traditions.

- Peter Dewood

LJ: When did you start producing your art?

PD: I’ve really only been doing for about 5 years. The artwork that I do is Sumi brush painting or Zen brush painting and it really stems from a deep tradition rooted in the practice of Zen Buddhism. In the olden days in China and Japan, traditional Sumi brush painting was very calculated and very detailed ink painting. This is a little bit different. Sumi brush painting is kind of a catchall term now. What I do is the Zen brush painting which called Zenga. It was used as a teaching method to convey teachings from Zen priests and monks. They would paint to use images and it’s executed very quickly, in one breath. And whatever it is, it is. It’s a very gestural and very alive practice. It catches the essence and the spirit of what they’re trying to convey.

LJ: How did you get into this particular genre?

PD: I started to take up Buddhist practice about 5 years ago and this is one thing within the practice that has always run through the bloodline. It’s not always taught and it’s not always something that’s included within the community, but there are various motifs and images all throughout Zen Buddhism: these abstract ink paintings. Whether it be the enso, which is the circle, which is a pretty common one that most people would probably recognize. I saw them in books and lectures and said to myself, “I don’t know if I need a teacher for this. I don’t know how I can pursue this, but this is what I know I want to do. I know I want to do this.” It was a very strong, grasping feeling I had for that. So I started on my own. Pieces started getting larger and I started practicing more and more and next thing you know it turns out that I’m not too bad at it actually. It’s something that I really enjoy.

LJ: So it’s more of a spiritual practice?

PD: It’s absolutely a spiritual practice, number one. But it’s still art. It’s both at the same time. But on the other hand the spiritual practice aspect of it is definitely the most important part for me.

LJ: Beautiful.

PD: That’s exactly what it is too, it’s a practice.

LJ: Are you affiliated at all with a Sumi brush society?

PD: I am not affiliated with that officially. But I have heard about it and people have suggested that I become affiliated with them.

LJ: We’ve donated to them in the past for their exhibits. They have a major show every year. We get a copy of their art catalog a couple of times a year. What I can do is put that aside for you so you can see the work that comes out of this society is amazing.

PD: Oh I can imagine.

LJ: Did you have to break free of something else to delve into what you’re doing now?

PD: Wow, that’s a really deep question…

LJ: Did you have to rebel and say, “I’m done with this, I’m doing that.”

PD: Growing up and becoming a teenager and finding out who we are at that age, I was always a musician. I played in bands and stuff and I was a skateboarder. I was just a punk kid. My folks weren’t really too excited about the idea that I was going out every night and playing in bands. I wouldn’t say I was a bad kid but it was just one of those things that’s like, “Oh that’s never going to pay the bills.” As I got older I was engaged in that lifestyle and there came a point where I just needed to settle down and I needed to rebel and break loose from myself. From my own ideas of what I thought I needed to be and it kind of progressed from there. When I started doing this art practice I was doing small pieces and it was very calculated and I was trying to emulate images I saw and copy styles and forms and as that grew over the years, the short few years I’ve been doing it, I’ve learned to trust myself and just let the artwork do itself. At this present time, as far as rebelling from anything outside of myself, I don’t have to do that anymore because I’m a grown man, I have a family and I pay my bills, so I don’t really have that issue in that department anymore.

LJ: Well many of the artists that we interview, they started with their painting in high school and they had family issues they had to overcome in order to study and to be what they wanted to be. So that’s just a different thing because of the timing. When you decide when you’re older, it’s not about rebelling against a parent, it’s about shutting down one area of your life and saying, “Okay I’m doing this now.” And maybe your friends don’t understand.

PD: Sure, and a very important thing to note is it’s really important for me and it’s a big part of the practice: it’s not necessarily rebelling or excluding anything. It’s very much inclusive. I don’t exclude anything in my life. That’s very helpful for this and for me. It’s really about not turning away from anything. It’s all happening all the time and I’m not separate from it. It’s really impossible and even detrimental to try to exclude or to block anything out.

LJ: What kind of studio space do you occupy?

PD: Currently I’m very fortunate to have a very large basement all to myself in my home. So I am 100% on site as far as my working space and my home, which is really nice

LJ: How do you light it?

PD: We have pretty good natural lighting, we have some windows down there. I don’t have any special lights or anything.

LJ: What kind of medium do you paint on? Do you paint on rice paper?

PD: Primarily it’s handmade mulberry paper from Thailand or cold pressed watercolor paper. I do a lot of stuff on canvas and I do some stuff on wood too. I kind of veered from the rice paper because it’s very thin and that’s geared a little more toward the more detailed very intricate Sumi brush painting.

LJ: So the mulberry paper is actually made from the pulp of a mulberry tree?

PD: Correct. It’s a pretty old technique. The paper is pretty hard to find, so when I can find it I try to buy it up as much as I can and if it’s unavailable then the watercolor paper is the next best. The absorbency is just right and the way it’s sized. So it’s really a nice medium.

LJ: Do you have to do anything to prepare it before you paint on it? Do you have to do a wash on it?

PD: You certainly can, but I don’t because most of the papers that I use are pre-sized. If I do canvas or wood I do treat it with gesso.

LJ: As far as your artistic process, how would you describe it?

PD: I generally go into the studio every single day and work. Sometimes I’ll force myself to go if I don’t want to, and I’ll work. Because the thing about it is that I never have any idea how these pieces are going to come out. It’s a very quick and precise process that I do. And when I’m done, I’ll just look at it. And I might have 5 or 6 sheets of paper lined up and I’ll do them all in a row and I’ll look at them and a lot of times I know right away, “I have something here and I don’t know why but I know this is something.” So I’ll set it aside. There’s also times when I think I have stuff that’s completely useless and I’ll discard it. I’ll never actually throw it away, I’ll just set it aside and come back and look at it later with a fresh set of eyes. It’s very important because it won’t always hit you right away. I’ve had times where I’ve done pieces and I’ve discarded them right away and I’ve regretted it because I think, “Oh I might’ve had something there.” So I’ve learned not to get rid of anything right away. This is just part of the process and the practice but I’ve also made pieces that were beautiful and I went back because I thought it wasn’t good enough and added to it and completely ruined it.

LJ: That’s not uncommon. A question we always ask is: “How do you know when you’re finished?” and that’s a real tough thing to know.

PD: And really there are times where if I go in to paint with a strong fixed idea of something that I want to execute and paint, ten times out of ten it comes out nothing like the way that I thought in my head. But if I’m really trying to do something specific in this style it just never works. It helps to come down into the studio with a fresh perspective, with the mind of a beginner. I always try to go and work and paint regardless. No matter what, I’m down there working on something, detailing something.

LJ: It sounds like you treat this as a daily discipline.

PD: Absolutely. I go down to paint every single day.

LJ: How many hours a day do you paint?

PD: Some days 3, 4, 5, hours. Some days, 15 minutes. Sometimes those 15 minutes are more productive than those 4 hours. It’s completely different and it’s really a part of the mystery of it and the practice because in the discipline of the practice, I learn so much every time I do it. It’s about the painting, but it’s not really about the painting. It’s much more than the painting. I get to see how I behave and my actions and my thought process in every aspect of my life through the painting. I get to see and notice when I’m irritated, when I’m tired, when I’m grasping to an idea and I need to let it be. Everything arises when I’m doing this, so my whole life is right there in front of me. That’s the real reward of this.

LJ: Do you feel like when you’re there, you’re totally in that moment?

PD: I’m completely in that moment and everything in my life arises. Every aspect of life is right there and that’s the real reward. I get to notice that and I get to see through exactly what it is and I have the opportunity to work on that while I’m working on the painting.

LJ: Are there any other artists in this genre that have inspired you in your line of work?

PD: My number one influence is Max Gimblett and he’s from New Zealand and he currently lives in NYC. He’s been doing this for many years. One day I got the courage enough to contact him and let him know how much of an influence he was on me and if I could send him a print. And to my surprise he was very eager to check out my work. I sent him a bunch of stuff and photos and turns out that he became a really big fan and supporter.

LJ: It’s amazing what can happen when you put yourself out there.

PD: Yeah, it really is. It was probably one of the biggest rewards. There are some really great traditional people – Kaz Tanahashi, this guy is modern, contemporary rather, but there are some other people who kind of pioneered this in the old days which is Hakuin. I try to connect with contemporary people who are doing this and this isn’t a huge thing that is really practiced widely, especially in the west. So to hear and be confirmed that I was someone who was really kind of continuing this tradition, along with a very small number of people, is very rewarding.

LJ: Do you deal with creative blocks? And if you do, how do you work through them?

PD: You know, generally if I have a creative block I’ll just kind of let it be for a little bit. I won’t ignore it necessarily. A creative block is never the art’s fault, it’s never the brush’s fault or the ink or paper. It always stems from what’s going on with me, what’s coming up and if I pay close enough attention—and that’s why meditation is really a key part of this—is if I’m lucky enough I can find it. I can get to the source of it—to the root and I can address it, and sometimes it comes quickly and sometimes it comes slowly but I kind of, without being too abstract, if I have a creative block, I just stop for a while. I’ll let everything run its course and when I’m ready, I’ll go back.

LJ: So you’ll take a break from going to the studio at that time?

PD: I’ll take a break from painting. I’ll always go to the studio and I’ll just be there. That’s kind of my space. I’ll light some incense and I’ll sit quietly and just be there with everything. I’ll at least just be there because that’s what helps me and that’s what I enjoy. But yeah, there are times when I don’t paint. It’s necessary sometimes. It’s not even to the point where I’m wasting ink and wasting paper, not every piece is fantastic, and it’s never a waste of time because I’m always learning something. I’m always able to kind of teach myself something. I’m not really too hung up on going and painting every day and having these masterpieces every time I’m down there because when I start doing that I kind of get a hang up and build dogma around having this idea of, “Oh I need to have all these great pieces” and that can be detrimental to any artist.

LJ: That can be stifling.

PD: Yeah, that can totally be scary when someone tells you how much they love your work and you just feel like you have to constantly produce amazing pieces and just amazing stuff and it just doesn’t work that way. There might be a little misconception to anyone who really doesn’t paint, this is the process. This is the painful, the self-doubt, the “I’m not good enough. I can’t possibly to anything better than this.” And you always do and you never know when it’s going to happen. You surprise yourself at all times. So yeah, to answer your question, I totally do take breaks.

LJ: Have you ever read the book “Art and Fear?”

PD: No I haven’t but it sounds like something I definitely need to get.

LJ: Pick it up! I just picked it up myself about a month ago and I think it’s a must read for anybody who does anything creative. I don’t care if you’re a painter, a writer, a sculptor, a business person, chef.

PD: That’s awesome, I’m going to get that immediately. That’s great!

LJ: It talks about how we put this pressure on ourselves because we are comparing ourselves to the true masters and really all we’re doing is we’re creating.

PD: And that’s really amazing because as artists, whatever our form is, we have a tendency to organize and build up dogma around that and we want to defend our space and our territory and as soon as we start to do that all sorts of problems start. We have problems with communicating with ourselves, we have problems communicating with others and I appreciate being eccentric and I appreciate that in everyone else, but the thing about, “Oh he’s just a weird artist”—that doesn’t appeal to me. Being approachable and a normal guy, I’m just like everyone else. I’m not just some weird artist and I don’t mean that in a derogatory sense at all. It’s just really like, “No I’m just a normal person. I’m not just holed up, trying to be crazy.” I get up every morning, I go to work, I have a family. This is really kind of part of my life. I don’t even consider it separate, it’s just something that’s so engrained at this point, it’s natural and it’s cool.

LJ: No artist has to defend a thing! I guess you have to if you’re in school and you’re getting critiqued or your exhibiting in a gallery and you are trying to tell your story so defending your work is like defining your work and saying, “This is what I’m trying to do, this is what it means.”

PD: Sure. I would go as far to say as this is not really defending, but I respect the tradition and I respect the craft and I feel that it’s a responsibility of mine to preserve it too. And to really not defile it. It’s still very important and it’s important to experiment and it’s important to be yourself and be creative. It’s important to me that I preserve that and give the necessary respect to the craft and its traditions. That may be where defending my art and defending my territory would turn in to the respect and the preservation.

LJ: How do you know when you’re finished with a piece?

PD: The piece tells me when I’m finished. Like I said a little bit before, I’ve ruined pieces by not trusting myself. The more I practice and the more I paint, I trust myself a lot more than when I started this because it takes practice and it takes discipline. The piece will generally tell you when it’s finished and you also have to trust yourself.

LJ: That’s a tough one.

PD: Yeah. Absolutely. So that’s certainly it. So trust your intuition and your heart. They are very big indicators. It’s a weird thing because you have to know how to identify your gut feeling and your heart, which is kind of the same thing, rather than your mind. Your mind is going to tell you all kinds of crazy stuff like, “Oh no this isn’t good enough, you need to add something here.” But if you can stop and kind of just be with it and be there and trust your gut and your heart, that’s the biggest indicator.

LJ: What does a typical day in your life look like?

PD: Generally it’s different. I work different hours every day. So I wake up, I do meditate. That’s the first thing I do. And if I don’t have to work that morning, I’ll work out for a while and I’ll go to work and some days I’ll get up and I have to go right to work, and I meditate later at night. Generally, I work on my painting in the evening time or at night and sometimes on my days off I do it in the morning. It’s always different. There’s really no black and white to what my days look like. They’re pretty scattered. I just try to wake up with positive feeling and outlook and that I’m going to do the best I can.

LJ: What do you consider your biggest accomplishment in your field so far?

PD: There’s so many that are important and rewarding.

LJ: What stands out as the one thing that you would want to share with your audience here?

PD: This is a little tougher to answer than I thought it would be. Certainly being recognized by one of my major influences like I said earlier, that’s definitely up there.

LJ: I would say that’s pretty cool.

PD: Yeah that’s probably it, being recognized by others in the Buddhist community as someone who continues this tradition and being regarded as someone who takes this very seriously.

LJ: Yeah, and approaches it skillfully. As you consider your work, how do you see yourself evolving?

PD: My pieces are getting larger and larger which is a big step from when I started. I used to do these really small paintings and I was trying to emulate what I was seeing other people do and as I practiced more and worked more, I learned to trust myself more and to let go of the idea that it needs to look a certain way. And that’s when I produce my best stuff. That’s when I completely and totally trust myself and I trust my materials. It kind of evolves as it evolves. But on a practical level without giving too much of a spiritual answer, I guess more shows, more exhibitions, really trying to get myself out there and trying to produce more publicly would be the evolving aspect of it.

LJ: Did you know that part of our new Showroom is going to be a gallery?

PD: I did not know that, that’s great!

LJ: We will talk more about that later. Maybe you want to do an artist exhibition and an artist talk.

PD: Awesome!

LJ: So how do you decide what to charge for your work?

PD: That’s the plight of the artist right there. When I started I would sell stuff for 20, 30, 40 bucks. I was excited that people actually wanted it. I thought, “Somebody’s actually going to hang this up in their home or office? That’s awesome!” I basically gave stuff away. I’ve been scolded by people, I’ve been stopped in my tracks and had people and fellow artists and people who know this game a little bit better than myself, kind of tell me, “You need to not give this stuff away like that.” And you don’t want to undercut yourself but at the same time you don’t want to price something so ridiculous that someone kind of looks at you like you’re being pretentious. I came to the conclusion that I charge what I feel it’s worth and if it’s framed properly, that’s all taken into consideration too. I take everything into consideration: the time that it took, everything. That one isn’t black and white. The pieces are different in price all the time. But I’ve been lucky, for the short time that I’ve been doing this, I’ve been able to do pretty well so far and I like to offer original work for a price that I believe is fair. And I also offer prints too, which is always an option. That’s a tough one.

LJ: So what kind of price range would you say?

PD: My lowest would probably be like $100 and my highest piece is probably $6,000.

LJ: So that’s a huge range.

PD: Yeah, it is a huge range. From where I started, up to this point, I would say that my lowest was like $40 I think. This is totally common thing in the arts community, the price is what you pay, the value is what it’s worth to you.

LJ: Exactly, yes!

PD: It’s important for me to be accessible as a person because generally someone is going to enjoy this more if they have a story attached to it. If they can know me and get to know me on a personal level. If someone sees this, it’s not the same way I see it. When it’s out of my studio and on the wall, it’s a completely different story. The audience is so important, artists go their entire careers and lives sometimes without even knowing how their audience feels about this stuff. So that’s the message that I put out there. I’m really conscious of my message and what I put out there or am intending to convey. It comes right down to what I title each piece. It’s really important that is open to interpretation. And it changes. I could look at a piece 6 months from now and it could be completely different. It changes all the time. If I can share that with someone else or if someone else shares that, that’s fantastic. I love hearing what it does to other people; what it is to them; how they feel about it.

LJ: Isn’t that the value in being accessible, that it’s not only them connecting with you but you get to feel good about, “Hey, I made this piece and I love this piece and this person is going to have it and enjoy it and now when I think of that piece I also think of that person who bought it.”

PD: Absolutely! I take that very seriously. They are human beings just like myself and they’re going to change and it’s going to grow with them, just like myself. That’s a huge reward in and of itself.

LJ: Are there any framing tips you’d like to share? Because your work is on our gallery and if you sell any pieces from our gallery, what would you like people to keep in mind, or does it not matter?

PD: It does matter. It’s crucial. The number one tip that I would give is to trust the experts, trust you guys because if you think it should be framed a certain way there’s a big possibility that that is the way it should actually be framed.

LJ: When someone is designing a framing treatment that they might want to buy off of our website, what would you tell that person?

PD: My preferred framing arrangement is float mounted on a nice light shade of rag board and a thin wood frame with an inch and a half border all the way around, no mat cut around it or anything like that and spacers are nice too. That’s my favorite way with the size I’ve been working with.

LJ: It’s been such a pleasure talking to you.

PD: Thank you! Likewise!