Artist Profile: Laurin McCracken

That’s an interesting spelling for a first name.

“I’m actually William Laurin McCracken,” explains its owner. ”My mother was a McLaurin, one of the four oldest clans in Scotland.”

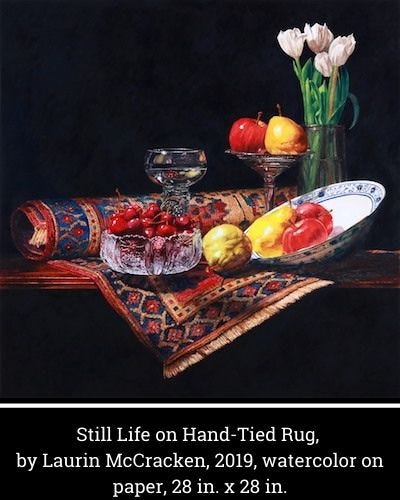

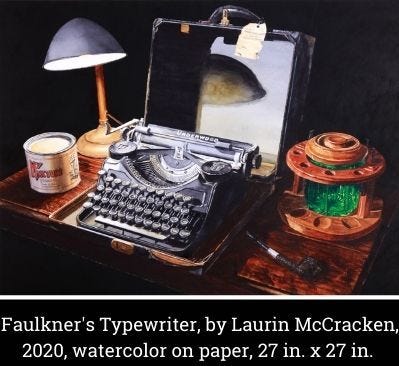

Laurin McCracken is talented, and driven. His still lifes, florals, and landscapes are startlingly realistic. The fact that they’re watercolors – a medium more frequently used to create impressionistic, rather than realistic, works – makes them even more astounding.

For 40 years, Laurin McCracken practiced architecture, his first love, after attending Rice University (B.A. in Art and Architecture) and Princeton (Master’s in Architecture and Urban Planning).

Now 78, McCracken didn’t start painting until he was 60, but has made every day of his second career count. He’s won countless awards, published numerous articles, been featured in many more, and has earned significant status in more than a dozen watercolor societies, including the American Watercolor Society.

Currently, McCracken lives and works in Fort Worth, Texas. He has been a friend of American Frame for more than a decade, and has conducted workshops at the company’s Toledo, Ohio headquarters.

American Frame: Where are you from originally?

Laurin McCracken: I grew up in little towns all over Mississippi. I’m a pure Scots-Irish product of the diaspora that took all the Scots-Irish out of Scotland, then to Belfast, then to the U.S.

When I was in the 7th grade, I knew I wanted to be an architect. In high school, I got a job working for the best architect in Meridian, Mississippi. My boss had gone to Auburn as an undergraduate. I didn’t know about having a “backup school,” so I only applied to Auburn. Luckily, I got in. While there, I earned a scholarship to Rice University in Houston. I had two more years to go to school, and since Rice offered a full scholarship, I went there rather than go back to Auburn. At Rice, I was in the ROTC program. I went into the military and extended my two years into three and spent most of that time in Germany. Then I went to Princeton for a two-year joint program in architecture and urban planning. After that, I worked in architecture firms in New York, Chicago, Dallas, and Washington, D.C. I never went back to Mississippi.

How long did you practice architecture before you became a painter?

I practiced architecture until I was in my late 60s, almost 70. I started painting the year I turned 60. I was living in Alexandra, Virginia when I started taking watercolor classes.

How do you describe your style?

I paint in a high degree of realism. Not photo realism, like some acrylic painters. It’s my interpretation of realism. One of my guiding quotes is by Henry Thoreau. “It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.” As an architect, you’re trained to see. The gothic cathedrals are a great example. From a distance, their handsome shape draws you in. The closer you get, the more detail you see, like the sculpture on the top of the flying buttresses. Then, you notice the arches of the windows. When you get up close, you see the texture of the stone and the carvings. It continues inside. At every point, there is another layer of detail to be appreciated. Everyone else sees the trees in the forest. I see the trunk of the tree, the limbs, leaves and veins on the leaves on the tree in the forest.

And in your paintings?

My paintings are painted to view in a gallery or home from about six to eight feet away, an optimum viewing distance. From there, you don’t see brush strokes. You just see the shape of that pear. I don’t paint every little dot on the pear. The viewer’s mind will do that because your mind knows what a pear looks like. If I can replicate the pear close enough to reality, you will see it as reality.

What is your creative process?

First I look for things that interest me and tell a story, things that have texture – glass, shiny objects, rough objects. For me, a typical painting is a still life composed of articles I’ve collected, or I go to friend’s houses and they let me use their silver, crystal and tablecloths.

I may take 100 to 300 photographs. Once I look at the photos on the computer, I find one that would make the best composition. I might adjust things a bit, move a jar to the left or change a highlight on a silver piece. I may change things when I paint.

I don’t just reproduce the photograph. I try to improve the story I’m telling until the last brushstroke.

Then, I project the image onto watercolor paper, which I’ve taped to the wall. I trace the image. When I project the image, I get so much more information about the details of an object.

Tracing can take four, six, even eight hours. It’s one thing that separates my style. I don’t mind the time it takes because that’s the only way I can achieve the result I’m looking for. Then, I put the drawing on my painting table. I won’t start the actual painting process immediately. Sometimes I wait six weeks or three months. It just percolates in the back of my head.

You have to figure out the sequence of painting. What do you paint first and what do you paint last? Traditionally with watercolors, you paint the lightest thing first, and the darkest thing last. If there’s something really complex in your painting, my advice is, paint it first. If you muck it up, you haven’t lost the whole painting. I haven’t mucked up a painting yet. I do a lot of test painting of colors and details before I paint them. It’s not unusual for me to spend 100 to 200 hours painting a painting, although a lot of that is drying time, waiting to continue.

Who do you admire?

My paintings are greatly influenced by the Dutch and Flemish still life painters of the 16th and 17th centuries: Willem Claesz. Heda, Jan Davidz de Heem, Pieter Claesz, Clara Peeters, and my number-one favorite, Willem Kalf. He’s famous for his dark backgrounds and strong graphic compositions. These artists recorded, in great detail, the growing affluence of the world around them. During their time, Dutch ships traveled the world and returned with new items of interest, like blue and white porcelain from China. We live in a similar age of affluence that should be recorded.

When was your first American Frame order?

Almost 10 years ago.

When I first started getting into watercolor society shows, I saw an American Frame ad. The watercolor world requires a simple black frame and white mat. That’s what I saw in the ad. I went online and ordered. I was very impressed with the quality of the product. The frame was as good as any frame I’d ever bought, and I’d bought frames for hundreds of dollars at the finest frame stores. The joinery at the corners, the quality of the wood, it was exceptional. But what really blew me away was the cutting of the mat. It was excellent. I’d been cutting my own mats. It’s not an easy thing to do. And the way they packaged the frame – they have a specially made cardboard container with a cradle that they set the frame. Then they pack it with polystyrene.

You’re a repeat customer, yes?

I don’t order from anyone else. They’ve framed maybe 400 of my paintings. When they created the system where you can upload your image and they print it on exceptional printers and papers — I recommend that to everybody. Every time I do a workshop, I recommend American Frame. I say it’s the easiest website to use and you’re going to see exactly what you get to buy.

One time, I called American Frame and asked to speak to somebody. I ended up talking to (American Frame President) Laura Jajko. About four years ago, she asked if I’d be interested in going to their headquarters (in Toledo, Ohio) and giving some talks. I went, I spent quality time with Laura, her sister (Dana, American Frame CEO) and their late father (Ron Mickel, company founder) and met most of the people in the plant. They’re great people.

What would you tell the watercolor world about American Frame?

Just use them. You’re going to find a frame you like and it’s going to be priced properly, packaged beautifully, and of the best quality. If you have a question, call them. They’re really nice, really intelligent, and they want to hear from you. They want to help you show your art at its best. They don’t want you to not buy a frame because you don’t understand something. Where else do you get service like that? Nowhere.