Artist Profile: Eric Hanson, Museum of Wisconsin Art

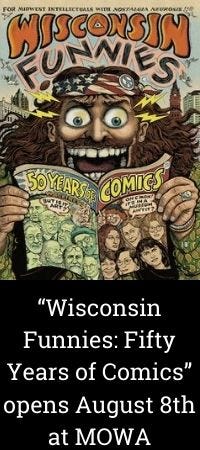

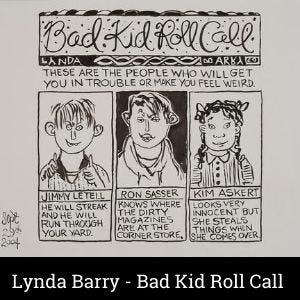

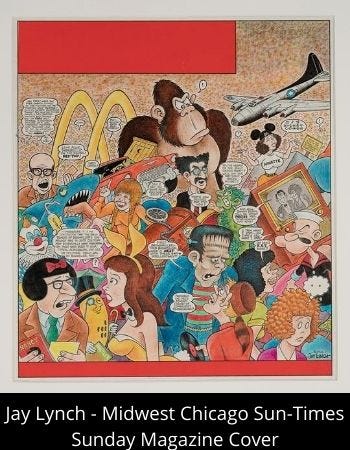

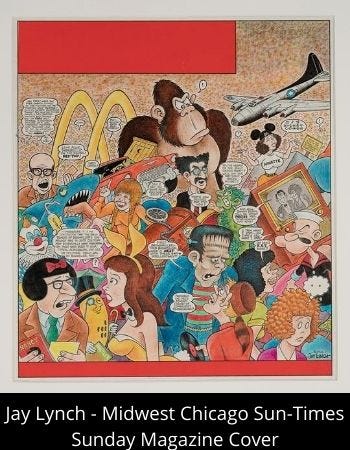

It’s July 2020. Eric Hanson, a preparator and exhibit designer at the Museum of Wisconsin Art (MOWA) in West Bend, is busy getting a new exhibition ready for an August 8 opening. “Wisconsin Funnies: Fifty Years of Comics” will include almost 200 works by more than 30 artists, including hand-drawn original art, comic books, alternative newspapers, and other collectibles.

Eric just received his order from American Frame. He seems pleased.

“Started to unpack frames this a.m.” said an email from Eric email to Craig, American Frame’s senior manager of sales and service. “They look almost hand finished! The corners look amazing considering they are a cut and join. You guys never cease to amaze.”

Eric, a Wisconsin native, wasn’t always into art.

“In high school, I took AP physics instead of art class,” he says. “I stopped taking art classes as soon as it wasn’t required.” Then, during his time at the University of Wisconsin Madison, “I took a photography class. That was my first break into the arts.”

American Frame: How did you become a preparator?

Eric Hanson: When I transferred to the University of Arizona in Tucson, I took a class called museum studies. I also got a side job as a gallery attendant at the CCP, the Center for Creative Photography. It’s an amazing place that was started by Ansel Adams, among others. The CCP’s preparator-slash-designer needed help changing up exhibits and asked me if I wanted to help. He saw that I was meticulous, clean and that I paid attention to detail. He offered me a job.

After I graduated, I continued working at the CCP. I was the main design preparator. My supervisor left, so I took his job. I also worked at a small frame shop where we framed a lot of high-end artwork. People came from California and New Mexico to have their works framed by us. Two full time jobs allowed me to pay off my student loans in nearly two years.

Then, a headhunter told me about a position at the Amon Carter Art Museum for American Art in Fort Worth, Texas.

How long were you at the Amon?

Three years. Up until then, my work was almost exclusively in photography and works on paper. The Amon had acquired a couple hundred thousand watercolors and needed someone with a background in photography to help with that.

What brought you back to Wisconsin?

When I was younger, I couldn’t wait to get out of Wisconsin. Once I spent some time away, I realized I really liked Wisconsin. I wanted to come back, but preparator jobs were few and far between. It’s a difficult occupation and involves moving around a lot. I finally got a job at the John Michael Kohler Art Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin.

What kind of museum is the Kohler?

Historically, it focused on Wisconsin self-taught or environmental artists, those who simply had the compulsion to create artwork. Then they expanded and started presenting more contemporary works. They’re really big on contemporary and experimental artists and installations. I was there for 17 years.

About a year ago, I moved to the MOWA.

What are the responsibilities of a preparator?

Basically, everything involved with the transportation, storage and display of any or all works of art.

You have to know how to build crates that will best protect the works in transit from temperature, humidity and vibration. You also frame, make captions, and design lighting.

What’s the best part of your job?

For everyone else, the number one rule about museums has always been “Don’t touch the artwork.” What’s cool about my job is I get paid to touch the artwork. I get to see the backside of a canvas, the notes that are written, doodles in the margins of a matted piece of work on paper.

What’s the most challenging part of the job?

That’s easy. The whole process of creating an exhibition involves curators selecting works, deeming them worthy of display. Then to the registrar, who’s in charge of transportation. They arrange shipping to the museum, and keep track of where everything is. The preparator gets to work last. Sometimes it’s easy, opening the crate and placing a sculpture on a pedestal. But often, it’s like the “Wisconsin Funnies” show we’re preparing for now. I have 200 works on paper that I need to mat and frame, and then install. The opening date never changes. So, if anything goes wrong – and something always does – it all falls on the preparator to make up for it quickly. We take for granted that there will be long days and weekends to get a show ready to open on time.

What does the general public not know about museums? What do museum professionals like you know that we don’t?

Most of the places I’ve worked at have become more female-dominated. In Sheboygan (John Michael Kohler Art Center), I was one of only a handful of men on staff. The vast majority were young females.

Another thing: 85 percent or more of the work that takes place in a museum takes place behind the scenes, in the back rooms, the basement, in offices. The work itself, the art on display, is just a part of what we do.

What free advice would you give amateur framers?

Keep it simple. For the upcoming “Wisconsin Funnies” exhibition, I’m using American Frame’s 206 Maple, a frame with a simple, clean profile. I don’t want people to ooh and ahh about the frame, I want them to ooh and ahh about the artwork. As always, I’m treating the artwork with respect.

How did you become aware of American Frame?

I discovered them when I was working in Sheboygan 15 or 16 years ago. At previous places, I had a woodshop. I made my own frames, basically from scrap wood. At the time, I didn’t have time and I needed a quick answer for high-end, high-quality frames. Metropolitan Frame is the gold standard. Their frames are handmade, hand-sanded. They’re flawless. I needed something like that, but at a much reduced cost. From my research, American Frame was by far the best quality at the best price.

Another advantage of American Frame is that I didn’t have to order my frames from one company, the matboard from another company, and buy glazing from a separate company. It all came together as a kit, already cut to size. All I had to do was get my artwork in there. That was huge, one of those moments, a game changer, basically.

What special challenges does your “American Funnies” exhibition present?

I was supposed to be matting and framing, and then COVID-19 changed everything. Now, I’m playing catch up, getting 200 works into 120 frames installed by August 8. Right now, I’m a little more than halfway through all the matting and the frames. I have four pallets with 140 American Frame frames out in the hallway.

As a preparator, how do you know when you’re doing a good job?

The better I do my job, the less likely it is that people know I exist. If you go into a museum and the lighting sucks, the pictures are all crooked, and there’s misspellings on the labels, you say to yourself, “Who the heck did this?” But if you go to a museum and everything’s perfect, you can focus on the art and enjoy the experience and not be distracted by imperfections in the gallery. You don’t even think about somebody doing the work. The kind of people who are interested in doing what I do need to be creative, meticulous, attentive to detail, very aware of their surroundings, but not "front-of-house" types who crave attention. We work behind the scenes. We're the all-important supporting cast of a truly amazing production.