Artist Profile: Dave Frieder

Dave Frieder has been photographing New York’s bridges since 1993, combining precision with art to represent his long-time fascination with these engineering marvels. He has learned that in order to be able to capture a subject on film, paper, or canvas, one must understand their subject fully. For Dave, being able to “Feel The Steel” was a way of understanding how and why bridges work and function.

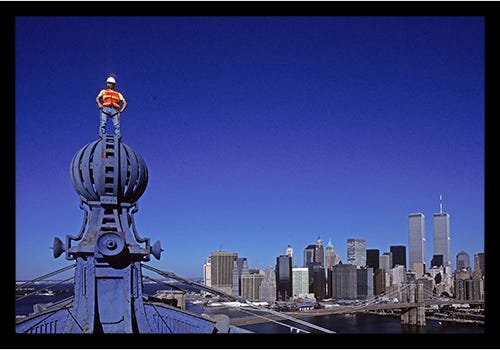

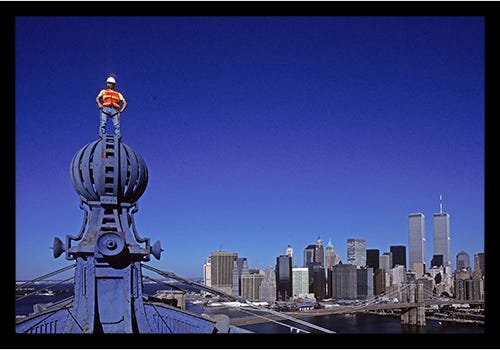

Self-Portrait of Dave Frieder standing on the Northern Most Sphere, of the Brooklyn Tower of the Manhattan Bridge

Involved with photography since the age of seven, Dave started off with a Kodak Brownie, experimented with early box cameras, and eventually bought his own 35mm. He was intrigued by a poster print of Ansel Adams’ “Moonrise,” which led him to an interest in how photographs could be manipulated—and a desire to find out more. Learning from the likes of Jeff Nixon, John Sexton, and Morley Baer, Dave developed his craft and worked to meld his love of photography with his admiration for bridges.

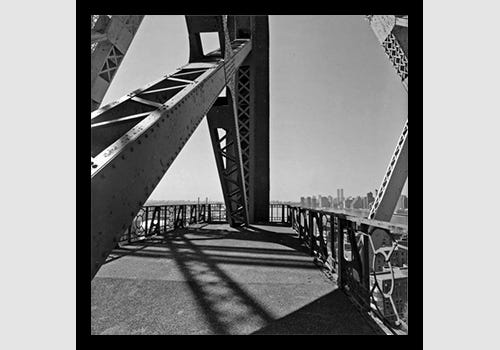

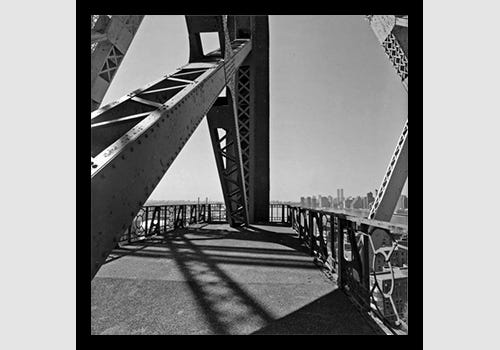

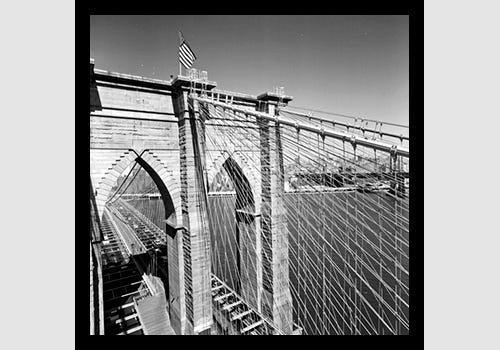

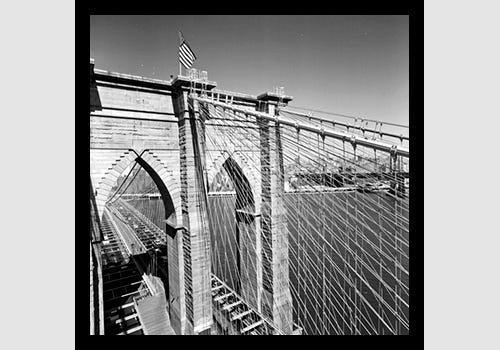

Brooklyn Bridge

Full View 1996

A decade of unprecedented access to climb and photograph every major New York City bridge culminated in Dave’s published book, The Magnificent Bridges of New York City. He also sells fine art prints of his work, which are wet prints that he processes in his dark room himself.

American Frame connected with Dave Frieder to find out more about his work and inspiration. Our insider interview provides a closer look at Dave’s photography journey, artistic approach, and personal insights.

On how he formed an interest in bridges:

I am actually from New York originally—Queens. I lived there until I was six years old, and I sometimes went with my father into Manhattan, over the Queensborough bridge to his place of employment. It was fascinating to go with my father to the city. In order to get there from the Northern Boulevard, we had to cross over what was (back then) the dual-bascule Flushing Bridge. A dual-bascule bridge has two leaves that open up. There’s one on one side, one on the other, and they lift open. When you're driving up to it, the bridge deck is facing you, and I thought, wow, that is fascinating. I was maybe two or three years old. Seeing it up in the air, watching it go down again and then driving over it, I was saying, wow, that is so cool! That's probably what got me started with an interest in bridges and engineering.

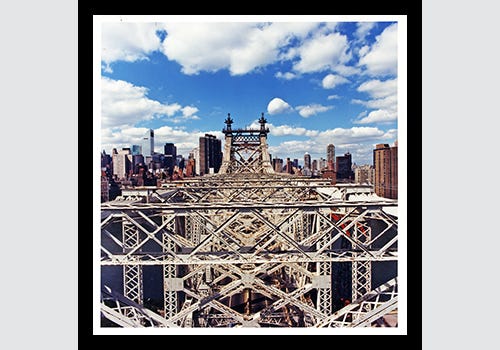

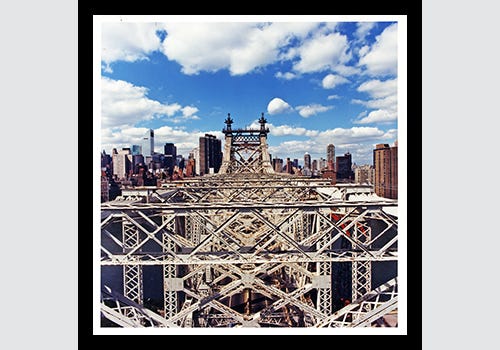

Queensborough Bridge

View from Center of Roadway Near Queens Tower 1995

Queensborough Bridge

View from Lower Balcony Platform Tower Number Three Looking South 1996

In 1959, we moved from Queens to Closter, New Jersey. To go to my father's work and to visit my grandparents, we had to cross the George Washington Bridge. What fascinated me about that is once you got off the bridge on the New York side, you had to take one of the vehicular tunnels to get to the Harlem River Drive. There were two tunnels: one at 178th Street (to go from Manhattan to the Harlem River Drive), and one going west at 179th Street to get back to the George Washington Bridge. I thought, wow, that is cool—a tunnel to a bridge, and a bridge to a tunnel. It reminded me of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, which was much longer (I think it’s still one of the longest vehicular tunnels in the world). I found that really fascinating, and the bridge always impressed me.

About the time we moved to Jersey, they started building the lower roadway. I said, wow, the engineer had enough insight to design a switch for a lower roadway, knowing that the traffic would increase. The lower roadway was originally designed for mass transit (four lanes of light rail), but that was changed to three lanes of vehicular traffic. Mind you, the center of the lower roadway is designed for air currents only (because of the lessons learned from the ill-fated Tacoma Narrows Bridge that collapsed in Washington). The air currents pass through and around the deck to keep the bridge from twisting or flexing. So I found that really fascinating, and all of it sparked my interest in bridges.

Taking the East River Drive to my father's parents on the Lower East Side of New York, we’d pass the swing bridges across the Hudson River. Then the Triborough Bridge, the Hell Gate, the Queensboro, the Williamsburg and the Brooklyn. And I was always fascinated looking at all these different bridges. They all looked different, but they served the same function. When we’d come to the Queensboro Bridge, I would look up and see the huge finials. And I said to myself, wouldn't it be cool to be up there someday? I had no idea that I'd be climbing these things!

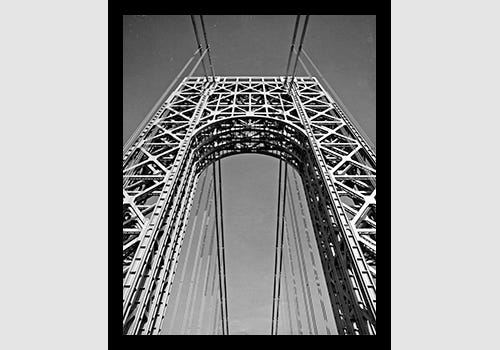

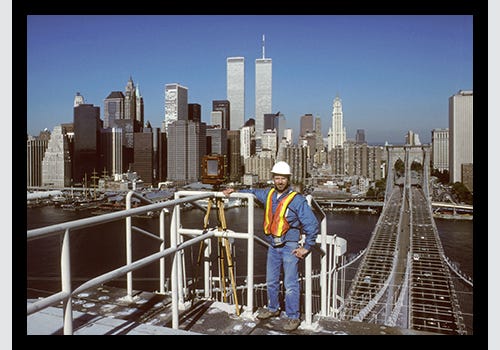

George Washington Bridge

Upward View New York Tower From Center of Roadway 1996

Hell Gate Bridge

Full View from Tribourough Bridge 1997

On his relationship with heights and the experience of climbing bridges:

Heights never bothered me for some reason. When I was a kid, my grandfather took me to the Empire State Building, and I was able to poke my head through the fencing they have up there. Looking straight down, I said, wow, look at that. My grandfather was scared to death, but it didn’t bother me. It looked so cool.

I will say there were a few bridge places where I could not hook up my safety harness, and the only way to hang on was with the tips of my toes and the tips of my fingers. In one case, that was the only way to get to a certain location. Once I got to that location, a fellow lowered my camera gear to me with a rope (I carried rope with me like a mountain climber). I hooked up my safety harness to the box beams, and I made the photographs. Then I put everything back into the backpack, he hauled it back up to the top of the bridge, and I slowly climbed back down. When I got back to the roadway level, he looked at me and said, you're crazy. I said, maybe I'm crazy, but I'm not nuts. I knew what I was doing. I was very careful. I had enough confidence in myself (and I had also done gymnastics for 20 years).

I've made over 100 bridge climbs of 22 bridges.

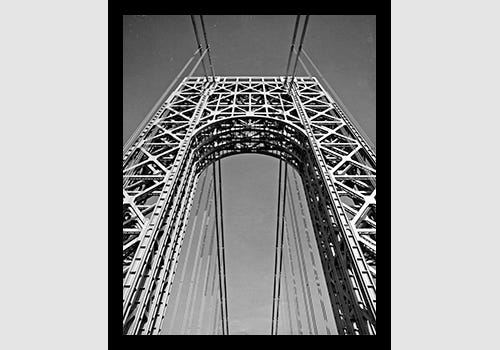

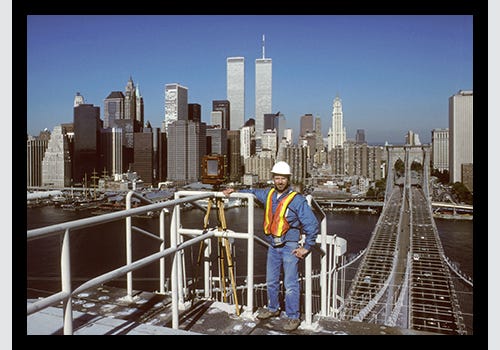

Dave Frieder standing on the Brooklyn Tower of the Brooklyn Bridge

Photo taken by NYCDOT Iron Worker

On how he got into photography:

My father had a little plastic Holiday Brownie camera, which he bought to take pictures of the house, our dog at the time, our garden, the flowers. And I borrowed it. At the time, it took 127 film. So I'm taking all these photographs, and I said, wouldn't it be neat to process the films myself? I realized after speaking to some people that black and white is a lot easier to process than color. I made this makeshift dark room in the basement—it didn't have a door, just some black sheets. I bought a little Kodak printing kit that was strictly for contact printing (I didn't have an enlarger), and I made prints of the photographs from this camera. The negatives, of course, weren't very large.

Then a kid in grammar school gave me a Brownie Six-16 camera. The negatives were pretty big, about the size of a postcard, and I was making prints from those. I thought this was really cool. And it continued for quite a while. My father had an old Kodak 35mm camera, which I used, and my mom bought a half-frame 35-millimeter camera (I think it was an Olympus Pen E). So instead of 36 exposures, you would get 72. I always had this interest in photography. It always seemed really cool that you could make a quick photograph. The shutter speed would be 250-500ths of a second, but it captured or projected an image on film. Then you’d process it, make a print, and there's your photograph. I thought that was really great.

Williamsburgh Bridge

Upward View of Manhattan Tower from Train Tracks 1999

Then I saw some photographs that John Sexton took of the Golden Gate Bridge. He took some great photographs on top of that bridge. I was also getting into photography by a fellow named Ron Wisner, who made my wooden field cameras.

And I said, wait a minute, where are there more bridges than anywhere in the world? Right across the river in New York city! There's an idea. So after all the begging, the pleading, the phone calls, going to the main branch of the New York public library, checking out possible books (there were no fine art coffee table books on New York's bridges), getting all the clearances and getting the proper insurance, I had 8-10 years of unprecedented access to climb and photograph every major New York City bridge.

On his preferred medium:

I still prefer the use of film to capture what I see and feel. Digital is nice, and it does have a purpose. I've seen how it's an incredible medium. But I prefer to have a negative to make a print. That's how I put my feelings into the photograph.

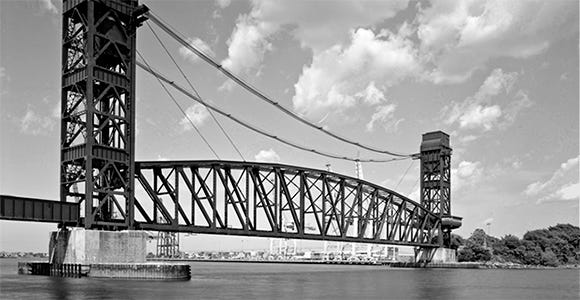

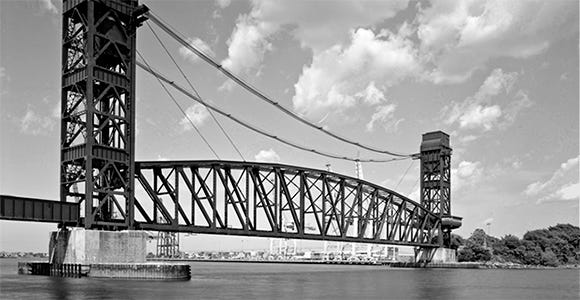

Arthur Kill Lift Bridge

Full View Closed Position 2011

On those who have influenced his work:

I took workshops with a few of Ansel Adams’ assistants. I had wanted to find out more about Ansel, since he’s what got me started in black and white. My father had bought a poster of Ansel's “Moonrise,” and he cut the lettering out and just had the image framed. He said, look at this great image. I'm looking at it and studying it, and I said, Ansel Adams … I've heard that name. So I did some studying on it and realized it’s a manipulated image, not a straightforward image. Ansel had burned and dodged the negative to make that print. That’s what really got me interested in black and white. I wanted to find out more.

So I called up the Ansel Adams Gallery in Yosemite, and they put me in touch with Jeff Nixon, who was Ansel’s workshop assistant. I took a two-week workshop with him. He introduced me to John Sexton, who was Ansel's personal assistant for many years. Then I was introduced to Virginia Mayhew, Ansel's oldest granddaughter. She actually came to an exhibit I had with some other folks in New York city. She introduced me to her mom, and from there, I met Jeanne Adams (Ansel's daughter-in-law), Michael Adams (Ansel’s son), and most of the other members of the family. They meant a lot to me because Ansel's work is really what got me started.

I’m also glad I worked with John Sexton because he envelopes the total scale, not just ten zones. Ansel Adams had worked with a fellow named Fred Archer to develop the zone system. It's a scale from zero to 10, from pure black to pure white. And you have the different zones of gray and black in between. I think there are thousands of shades of gray in between the pure black and pure white. And John does that in his work. I try to duplicate it.

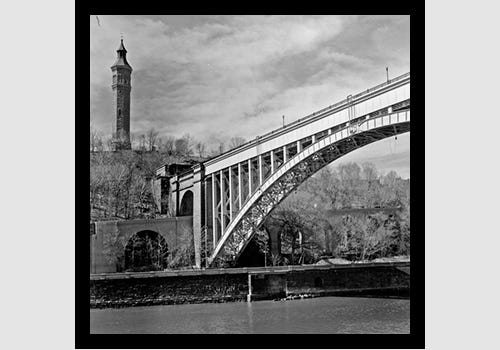

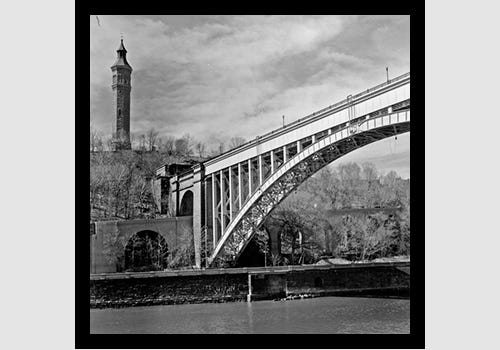

Aqueduct Bridge

Steel arch, water tower and clouds taken from Bronx side 1995

Henry Hudson Bridge

View from Center of Lower Roadway Looking South 2010

Some photographers, they're only black and white. There's no intermittent or intermediate shapes, and it doesn't have any feeling. It's just a black-and-white photograph. But when you put your feelings and emotions into the image, it totally conveys what you saw and felt. That's what I love about Ansel's work. My favorite of all, of course, is “Moonrise.” I've seen the negative, and it's pretty amazing what he did to create that image.

In a workshop with Jeff Nixon and John Sexton, I also met a fellow named Morley Baer. I really clicked with Morley. His work was phenomenal, absolutely gorgeous. I have one of his photographs. He really liked me and said some positive things about my bridge project. He wanted to see it when it was done. Unfortunately, he passed, but he had some great words of wisdom for me, which I treasure. I still have that letter he wrote to me.

These people meant so much to me. And when I finally did my bridge project, it was such an honor to give all these people a copy of my book. I wish I could have given a copy to my parents, but they had passed. I have a major list of so many people that helped contribute to the project, and without their help, it would not have been possible. This includes all the bridge authorities, people that gave me important information, friends—it was really a team effort.

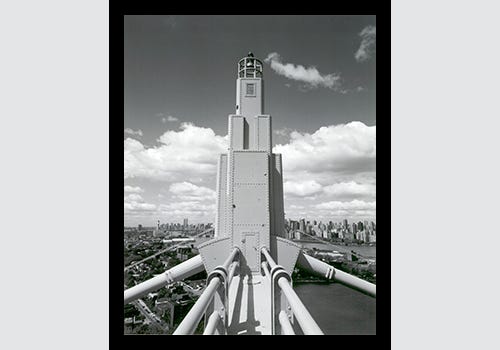

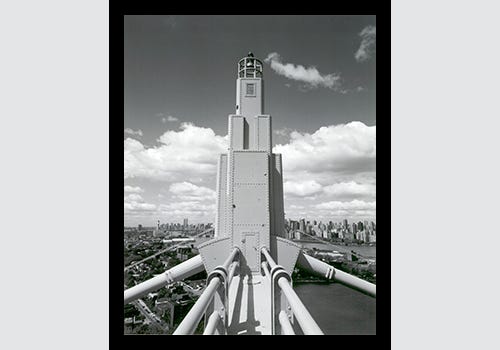

Triborough Main Span

Saddle Housing Aviation Beacon and Clouds 1997

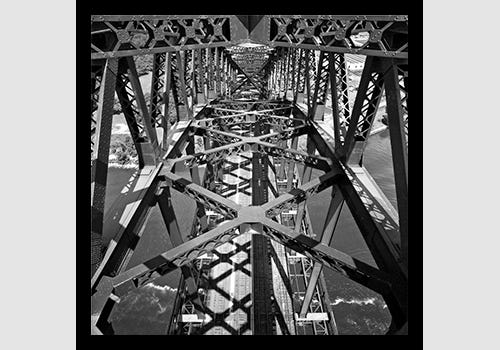

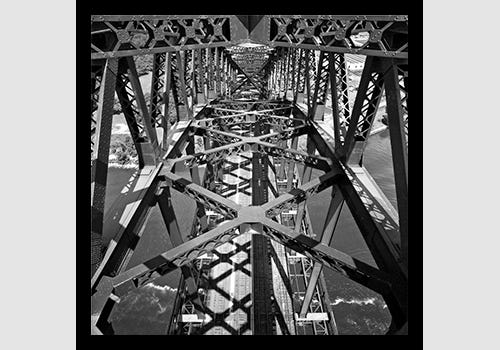

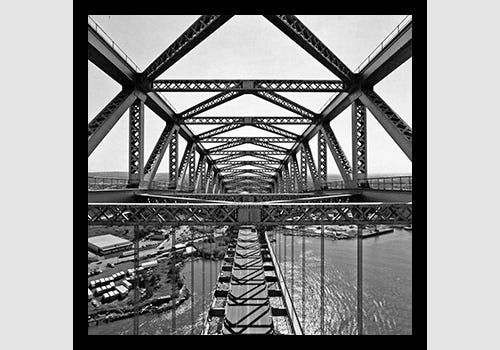

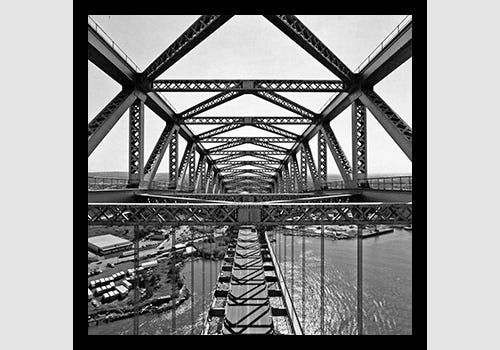

Hell Gate Bridge

View Through Trusswork 1996

On his most well-known image:

It was a cloudy, cool, somber day. And I'm on top of Manhattan Bridge. I remembered somehow that the clouds might clear in the afternoon. So I'm on top of the Brooklyn Tower, walking up and down the cable a few times. I have my Hasselblad with me (with the gyro), and the 35mm. I noticed the sky started clearing, and the winds picked up to about 10 miles an hour. I looked north, and the sky totally cleared. Deep blue sky, and I saw these white clouds coming south.

I said, oh, wow, I’d better get on top of the spear if I want to get anything decent. I got upside down to climb up the section of steel, which I used like a rung ladder. Once I stood up there, I hooked up my safety harness as the clouds moved across the bridge.

I'm looking across the other three spheres (lineals) from the Northernmost sphere on the Brooklyn Tower. And the motor drive was working great, so I'm firing away multiple exposures as the clouds are coming across. This was in color, and I quickly switched the magazines—put in the #8 Light Yellow filter because I wanted a little more contrast. I took exposures of the clouds coming across Southern Manhattan. Then, the clouds disappeared. And that moment was gone forever.

This was 1997. So, of course, the great Twin Towers were standing tall and proud. This image, you'll never see it again.

Manhattan Bridge

View of Lower Manhattan Skyline from Top of Sphere, Brooklyn Tower, 1997

On his knowledge of bridges:

As I was photographing bridges, I found them fascinating. So I must have over a hundred books on bridges and engineering, all those subjects. And I’ve studied every rivet, every bolt, every bridge in New York City. I’ve been studying this for decades.

The former chief engineer of the Port Authority, Frank Lombardi, once told me, Dave, I am very impressed with your knowledge of bridges and civil engineering. And I flipped. I said, Oh my goodness. That is amazing. He put that in a testimonial in the book. Great engineers appreciated my work enough to do that for me. I can't thank them enough. I mean, these guys are great—absolutely amazing folks.

Queensborough Bridge

Sea of Steel View of Trusswork Across Roosevent Island 1997

On which artist in the history of the world he would want to meet and why:

I’d like to meet Van Gogh. His work just blows me away. Back then, he barely sold two images, I think, and had a vision problem, but some of his work is so serialistic. I love his “Starry Night.” I’ve seen it—the real image—at MoMA. I’ve looked at it super close, seeing where there’s paint, where there’s not paint, the brush strokes, how he mixed the paints to get certain colors and textures. All of his work is just phenomenal.

On his biggest challenge as an artist:

My biggest challenge is some of the bridges—for instance, the Brooklyn Bridge. I like the Brooklyn. It’s cool. It's stone. It's one of a kind, more or less. But everyone, including their grandmother, has photographed the Brooklyn Bridge. So it was hard to photograph that and show it in a different way.

Also, Throggs Neck Bridge. It's a really neat bridge, but the arch is flattened. It's not a perfectly curved arch, like GWB or Whitestone. So that was really hard to put onto film and show how different it is. But I was able to get on certain areas of the bridges, where I could say, okay, this would look different, that would look different, let me just try taking this photograph, just for giggles. And it worked pretty much.

Brooklyn Bridge

Brooklyn Tower Main Cables and Suspenders 1996

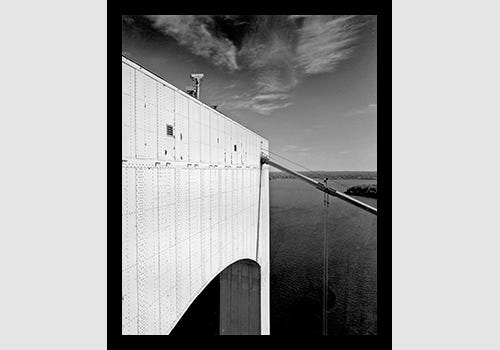

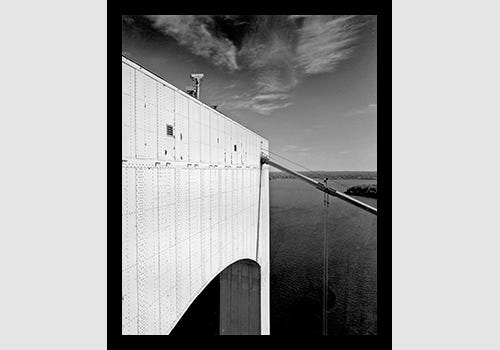

Throggs Neck Bridge

Face of Queens Tower and Clouds 1998

On how he discovered American Frame:

Actually, looking through the Internet. I couldn't find a decent place that made the frames I wanted. I looked up different framing on Google, and I said, wow, this company has the frames that I want. My father had some original Hirschfeld etchings, and I wanted to duplicate the frames because the others were damaged during my move to Pennsylvania. And I said, this is great, they have the frames I want. So I bought the frames and then I needed some more plexiglass. American Frame had what I needed.

On what piece of advice he would give to artists reading his story today:

Unfortunately, a lot of people give up too easily. When I was working on the bridge project (and this was before 9/11), other people wanted to go up on the bridges. I said to them, look, keep trying, keep calling the bridge authorities. Keep bugging them. Don't take no for an answer. And one fellow said, they keep telling me no. I said, well, don't give up. Give them a legitimate reason why you want to go up on the bridge and photograph. Tell them why it’s important.

Bayonne Bridge

Center of Lower Chord Looking South 1997

For additional information about Dave Frieder and his work, you can visit www.davefrieder.com, or check out his book at davefrieder.com/the-book.